Notas del libro “Architectural Ethnography” de Atelier Bow-Wow

MICHAEL HAYS: «[…] ‘[the space of representation is] planned anteriorly and [the space of occupation is] observed posteriorly.’ So you have two spaces: the space of building materials and techniques, and the space of human activity and interaction. These spaces correspond to two times–the ‘before’ of conceptualization and construction, and the ‘after’ of occupation. These two realms are brought together in the architectural imagination, having been triggered by a very particular kind of anatomic drawing showing the internal processes of architecture. […]»(p.6)

MOMOYO KAIJIMA: «[…] ‘[the space of representation is] planned anteriorly and [the space of occupation is] observed posteriorly.’ So you have two spaces: the space of building materials and techniques, and the space of human activity and interaction. These spaces correspond to two times–the ‘before’ of conceptualization and construction, and the ‘after’ of occupation. These two realms are brought together in the architectural imagination, having been triggered by a very particular kind of anatomic drawing showing the internal processes of architecture. […]»(p.9)

MOMOYO KAIJIMA: «[…] We asked the students to imagine possible behaviors of people in these spaces, and to draw ideas for the future. […]»(p.11)

MICHAEL HAYS: «[…] What is the relationship between the form of architectural elements and the occupation of space? Do you think there is a code or formula or template that defines the way they influence one another? […]»(p.12)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «[…] architectural elements and devices (roof, wall, floor, column, window, staircase, etc.) always work, play, and coexist with non-architectural elements (rain, sun, wind, gravity, body, trees, earth, etc.) in a specific place and time. Of course for construction we need precise drawings that define all the details. But we shouldn’t ignore that all these non-architectural elements are part of the ecology of livelihood […] the relationship between construction and occupation is similar to the relationship between thesis and antithesis in dialectics. The growth of the construction industry in the 20th century has reinforced this division. In vernacular architecture, there is a less distinct separation between construction and occupation, since both are parts of spatial practice for the ecology of livelihood. We listen to people and observe their behaviors–with a lot of passion–to understand what is really happening in each context. (Pause.) Every place reveals unique behaviors that are shared among the people who are part of that place. These behaviors are not something we can design. They are already there. We can only encourage or intensify them by intervening in existing conditions that define the behavioral capacity of the space. When we design something to encourage certain behaviors, it causes people to recognize that their behavior in that place is unique. It’s like a chicken and egg. (Pause.) We design by listening to the voices of the users, and learning how they organize their lives. Architectural design can spotlight a certain behavior by accounting for it in its decision making. In that sense, design through architectural behaviorology resembles ethnographic studies.»(p.13,15,17)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «[…] We perceived typology as an integration of different considerations of natural behaviors, of people’s behaviors, of social systems, etc., as one physical entity. […]»(p.23)

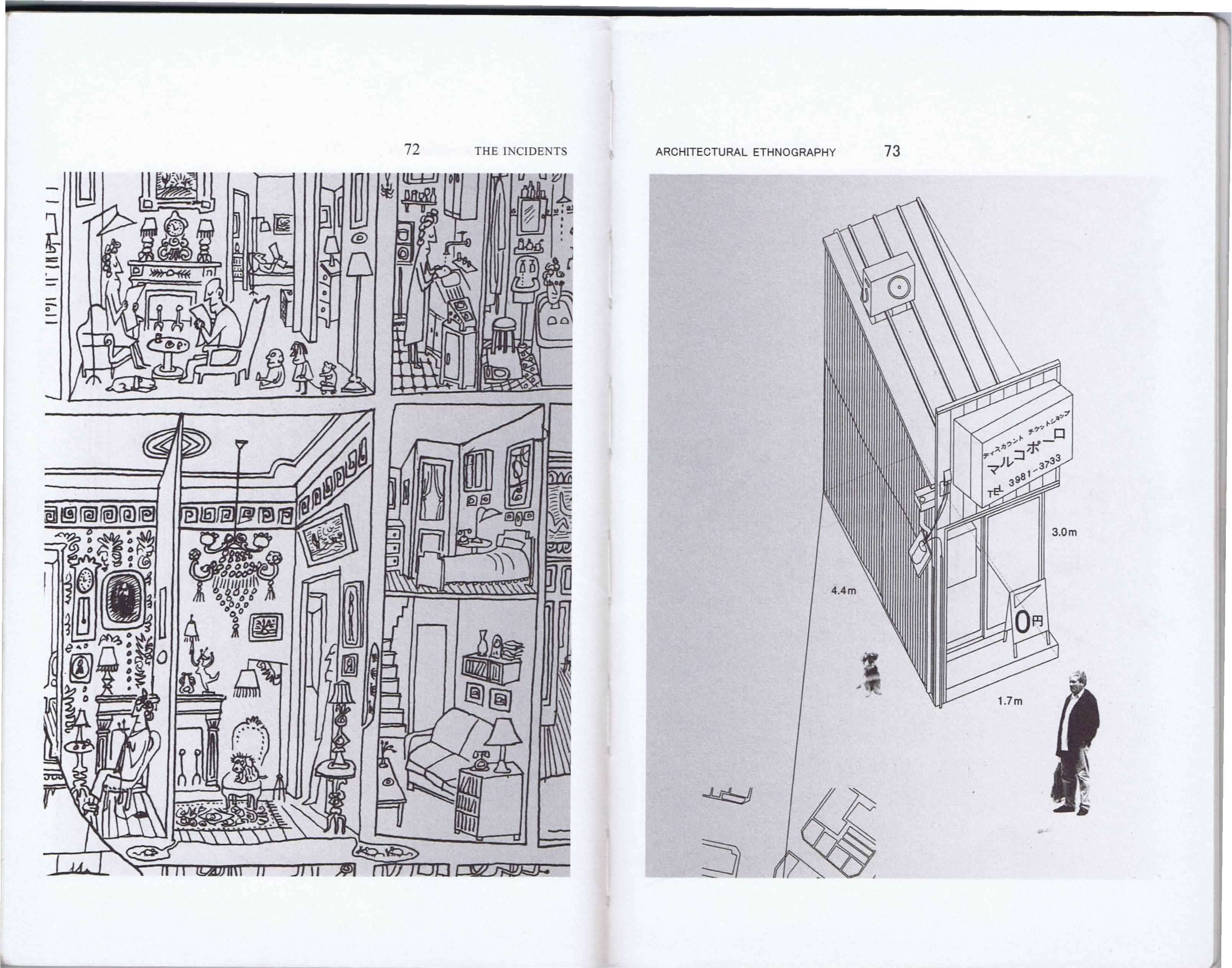

MICHAEL HAYS: «[…] Because in your drawings I see that people and things–tools, appliances, equipment–are brought to the same plane of consideration. It’s not just ethnography; it’s also ‘thingography’ or resography. You often don’t distinguish between human occupation and occupation by plants or even inanimate objects. […]»(p.24)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «[…] When an interaction repeats and becomes sophisticated, it is recognized as human behavior […] There are three modes of common tools: Res Communis (natural resources), Lex Communis (physical tools, instruments, and architectural devices that allow better accessibility to the resource), and Praxis Communis (the repetitive form of behavior produced by interaction with resources). […]»(p.27)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «The graphic tells us how to see things. […] What you draw is what you see. You work according to what you see. Then you need unique graphics to represent what you see. This coordination of the formality of the drawings with the content is an important message. If they don’t match, the message becomes very weak. […] Drawing represents the ecology of things for architecture that is drawn. It also means the ecology of things can be taken into account in architectural design.»(p.29,31)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «It’s a kind of democracy–to involve people as much as possible in graphic representation. Hand drawings are very democratic, very close to the experience of daily life–part of the ecology of livelihood. […] the democracy of architecture.»(p.35)

AUDIENCE [NAMIK MACKIC]: «[…] drawing as a form of solidarity with the physical forces that animate the environment […]»(p.36)

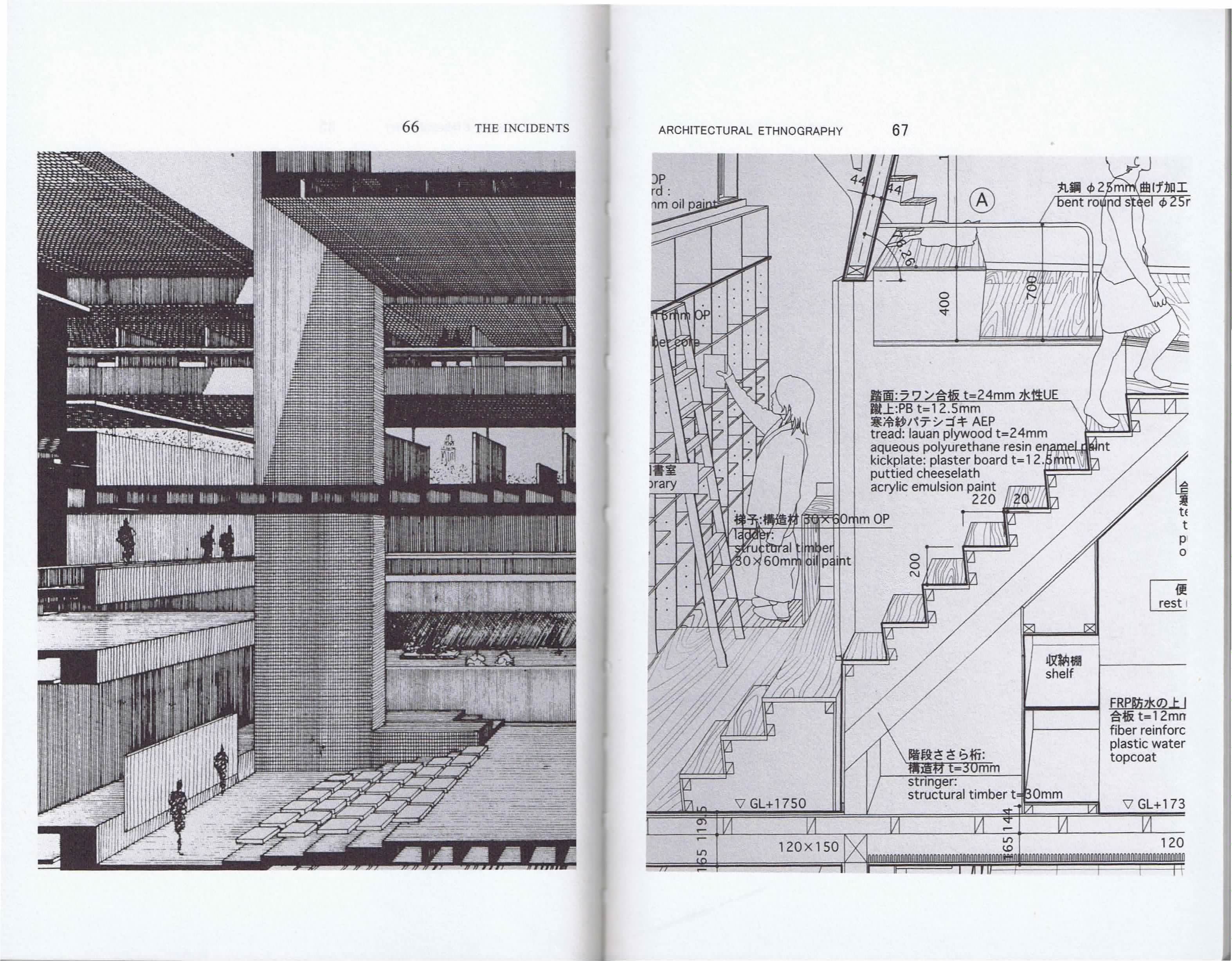

AUDIENCE [JENNIFER BONNER]: «[…] Someone like Mies van der Rohe illustrated materiality in one-point perspective by combining line and image, and there was only a slight hint of occupation in those drawings. And then Paul Rudolph drew the section perspective’s materiality as illustrated by lines and shadow–and that’s where occupation starts to get more intense. And then you draw materiality with only the single line. And the single line has no shadow; there is no collage necessary. That single line is also the line that you use to draw the architecture. […]»(p.38,40)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «We always avoid the modeling technique of using a shadow to illustrate the three-dimensional volumetric perception. […]»(p.41)

MOMOYO KAIJIMA: «Why? The simple answer: the articulation of depth, of the shadow, requires more training.»(p.41)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «We avoid the world of light and shadow, and the contrast between the two, even though it has been very important for the beauty of architecture for a long time. We are shifting the scope to the ecology of things that surround us–the ecology of livelihood. We also combine different moments in time within one drawing. So while a house might be lived in by three or four people, you might see six or seven people in one drawing, demonstrating different living behaviors. This articulation of simultaneity is important. Shadow and light are more about showing one particular dramatic moment of space.»(p.41,43)

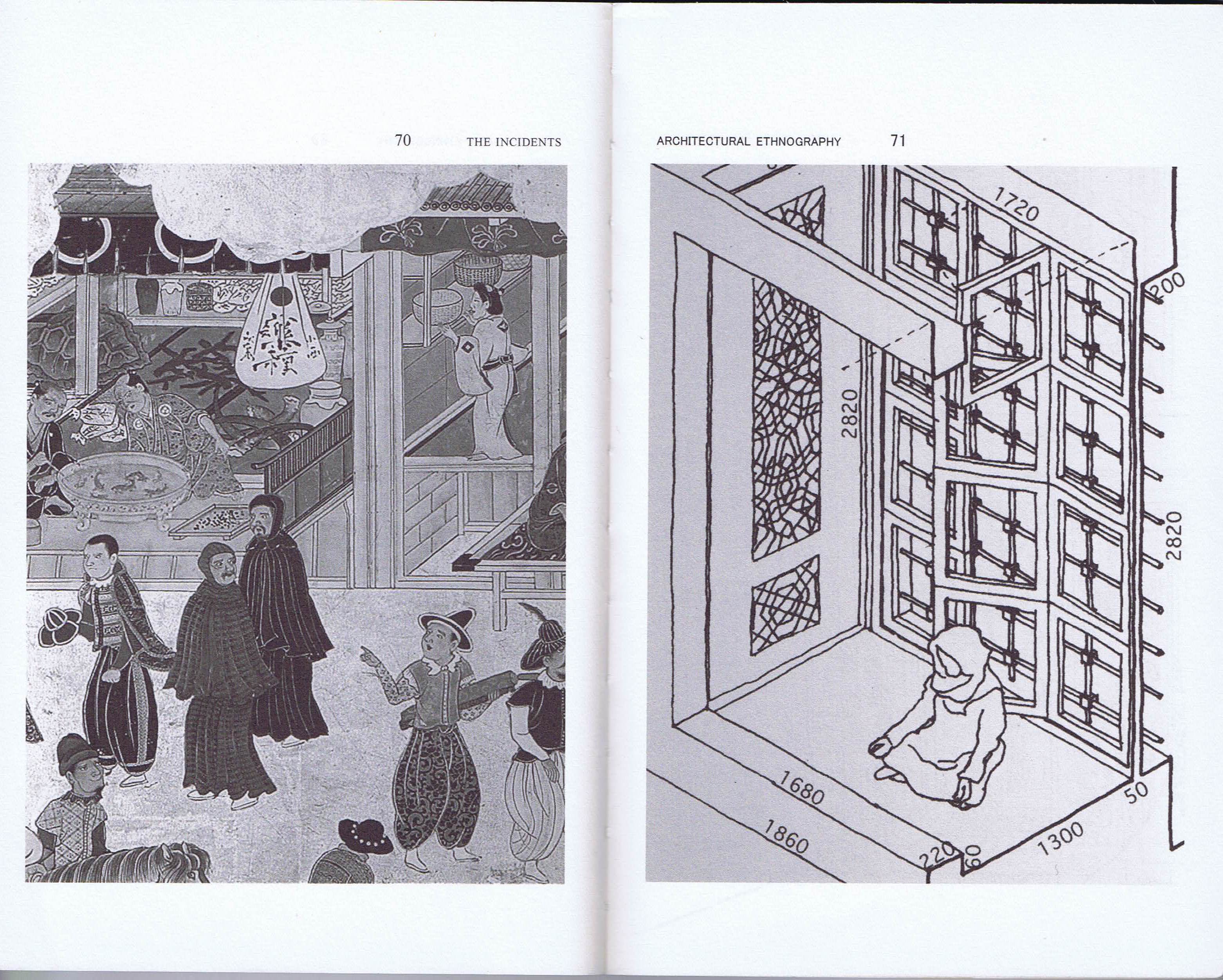

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «The window allows us to observe different types of behaviors gathering and interacting in and around architecture. The design of the window coordinates those behaviors within one physical entity. Windows are very intelligent objects in architecture. (Pause.) The WindowScape series was a means to develop our idea of behaviorology. Behaviorology is a way to understand architecture as an ecological medium. A window is obviously a product within a certain style. But it allows light and wind to come in, and causes people to act in a certain manner or to exhibit certain postures. The window is a merging of behavior and form in one physical expresion. […]»(p.49)

AUDIENCE [LAURA WAINER]: «[…] Your techniques and your drawings are amazing tools with which t understand the power relationships that are embedded within space. […]»(p.50)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «Architecture always exists together with noise. In construction drawings we don’t need noise–we don’t need human figures; we don’t need plants next to the windows; we don’t need the building next door. We just need materialistic description such as the thickness of the wall and its profiles composed by different materials within it–insulation, plywood, membrane, air, etc. But in our drawings, we can introduce noise, which is not a proper element of architecture. And the behavior of people is also noise. Construction drawings are obviously important, but they represent a moment when the producer governs everything. So the power is on the side of the producer or provider. But drawings can integrate many different things, many different times, and many different actors, which all perform in the building or around the building. And this relativizes or equalizes the power balance among the different elements that relate to the existence of the building.»(p.53)

MOMOYO KAIJIMA: «We call this noise, but in fact these are very important sounds. Now, the institution, our government, the older industrial system, thinks that design is always established by the more hardware–based aspect of the architecture. But we are interested in making the process more dynamic. So we need sounds that have the power to create our future space.»(p.53)

YOSHI TSUKAMOTO: «[…] Architecture design is still dealing with these ethnographic aspects of life in the modern city, while utilizing the industrialized network. In that sense, the contrast between the ethnographic network and the industrial society network can be relevant to drawing our self-portrait. […]»(p.57)

66. Paul Rudolph, Yale Art and Architecture Building, 1970.

67. Ako House (2005), Graphic Anatomy Atelier Bow-Wow, 2007.

70. Kano School, Six-fold screen depicting the arrival of a Portuguese Nanban ship, 17th century. (Christie’s Images / Bridgeman)

71. Sultanahmet Camii (2007), WindowScape: Window Behaviorology, 2010.

72. Saul Steinberg, Doubling Up, 1946. (The Saul Steinberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

73. Marco Polo, Pet Architecture Guide Book, 2001.

Atelier Bow-Wow. (2017). Architectural Ethnography. USA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Sternberg Press.